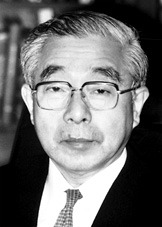

Kenichi Fukui

Kenichi Fukui (福井 謙一 Fukui Ken'ichi) was a Japanese chemist.

Fukui was co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1981 with Roald Hoffmann, for their investigations into the mechanisms of chemical reactions. His work focused on the role of frontier orbitals in chemical reactions: specifically that molecules share loosely bonded electrons which occupy the frontier orbitals.

Fukui was born in Nara, Japan. In his student days between 1938 and 1941, Fukui's interest was stimulated by quantum mechanics and Erwin Schrödinger's famous equation. He had developed the belief that a breakthrough in science occurs through the unexpected fusion of remotely related fields.

In an interview with The Chemical Intelligencer Kenichi discusses his path towards chemistry starting from middle school. "The reason for my selection of chemistry is not easy to explain, since chemistry was never my favorite branch in middle school and high school years. Actually, the fact that my respected Fabre had been a genius in chemistry had captured my heart latently, the most decisive occurrence in my education career came when my father asked the advice of Professor Gen-itsu Kita of the Kyoto Imperial University concerning the cause I should take.” On the advice of Kita, a personal friend of the elder Fukui, young Kenichi was directed to the Department of Industrial Chemistry. He also explains that chemistry was difficult to him because it seemed to require memorization to learn it, and that he preferred more logical character in chemistry. He followed the advice a mentor that was well respected by Kenichi himself and never looked back. During that same interview Kenichi also discussed his reason for preferring more theoretical chemistry rather than experimental chemistry. Although he certainly acceded at theoretical science he actually spent much of his early research on experimental. Kenichi had quickly completed more than 100 experimental projects and papers, and he rather enjoyed the experimental phenomena of chemistry. In fact, later on when teaching he would recommend experimental thesis projects for his students to balance them out, theoretical science came more natural to students, but by suggesting or assigning experimental projects his students could understand the concept of both, as all scientist should. In 1943, he was appointed a lecturer in fuel chemistry at Kyoto Imperial University and began his career as an experimental organic chemist.

In an interview to New Scientist magazine in 1985, Fukui had been critical on the practices adopted in Japanese universities and industries to foster science. He noted, "Japanese universities have a chair system that is a fixed hierarchy. This has its merits when trying to work as a laboratory on one theme. But if you want to do original work you must start young, and young people are limited by the chair system. Even if students cannot become assistant professors at an early age they should be encouraged to do original work." Fukui also admonished Japanese industrial research stating, "Industry is more likely to put its research effort into its daily business. It is very difficult for it to become involved in pure chemistry. There is a need to encourage long-range research, even if we don't know its goal and if its application is unknown." In another interview with The Chemical Intelligencer he further elaborates on his criticism by saying, "As is known worldwide, Japan has tried to catch up with the western countries since the beginning of this century by importing science from them." Japan is, in a sense, relatively new to fundamental science as a part of its society and the lack of originality ability, and funding which the western countries have more advantages in hurt the country in fundamental science. Although, he has also stated that it is improving in Japan, especially funding for fundamental science.