Amiri Baraka

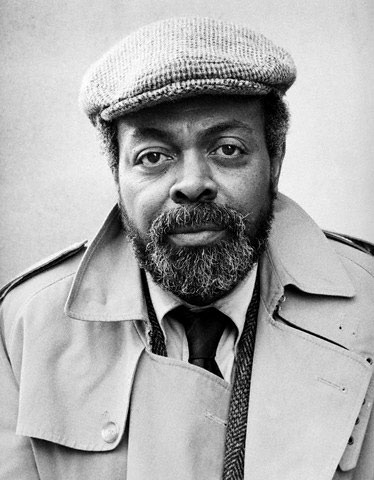

Baraka was born Everett LeRoy Jones in Newark, New Jersey, where he attended Barringer High School. His father, Coyt Leverette Jones, worked as a postal supervisor and lift operator. His mother, Anna Lois (née Russ), was a social worker. In 1967 he adopted the African name Imamu Amear Baraka, which he later changed to Amiri Baraka.

The Universities where he studied were Rutgers, Columbia, and Howard Universities, leaving without a degree, and the New School for Social Research. He won a scholarship to Rutgers University in 1951, but a continuing sense of cultural dislocation prompted him to transfer in 1952 to Howard University. His major fields of study were philosophy and religion. Baraka also served three years in the U.S. Air Force as a gunner. Baraka continued his studies of comparative literature at Columbia University. After an anonymous letter to his commanding officer accusing him of being a communist led to the discovery of Soviet writings, Baraka was put on gardening duty and given a dishonorable discharge for violation of his oath of duty.

The same year, he moved to Greenwich Village working initially in a warehouse for music records. His interest in jazz began in this period. At the same time he came into contact with Beat, Black Mountain College and New York School poets. In 1958 he married Hettie Cohen and founded Totem Press, which published such Beat Generation icons as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.

Baraka visited Cuba in July 1960 with a Fair Play for Cuba Committee delegation and reported his impressions in his essay Cuba libre. He had begun to be a politically active artist. In 1961 a first book of poems, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, was published, followed in 1963 by Blues People: Negro Music in White America—to this day one of the most influential volumes of jazz criticism, especially in regard to the then beginning Free Jazz movement. His acclaimed controversial play Dutchman premiered in 1964 and received an Obie Award the same year.

After the assassination of Malcolm X (1965), Baraka left his wife and their two children and moved to Harlem. His revolutionary and now antisemitic poetry became controversial.

In 1966, Baraka married his second wife, Sylvia Robinson, who later adopted the name Amina Baraka. In 1967 he lectured at San Francisco State University In 1968, he was arrested in Newark for allegedly carrying an illegal weapon and resisting arrest during the 1967 Newark riots, and was subsequently sentenced to three years in prison; shortly afterward an appeals court reversed the sentence based on his defense by attorney, Raymond A. Brown. That same year his second book of jazz criticism, Black Music, came out, a collection of previously published music journalism, including the seminal Apple Cores columns from Down Beat magazine. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Baraka courted controversy by penning some strongly anti-Jewish poems and articles, similar to the stance at that time of the Nation of Islam.

Around 1974, Baraka distanced himself from Black nationalism and became a Marxist and a supporter of third-world liberation movements. In 1979 he became a lecturer SUNY-Stony Brook's Africana Studies Department. In 1980 he denounced his former anti-semitic utterances, declaring himself an anti-zionist.

In 1984 Baraka became a full professor at Rutgers University, but was subsequently denied tenure.In 1989 he won an American Book Award for his works as well as a Langston Hughes Award. In 1990 he co-authored the autobiography of Quincy Jones, and 1998 was a supporting actor in Warren Beatty's film Bulworth. In 1996, Baraka contributed to the AIDS benefit album Offbeat: A Red Hot Soundtrip produced by the Red Hot Organization.In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Amiri Baraka on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.